ESSAY BY ERIK BLUHM

OPENNESS

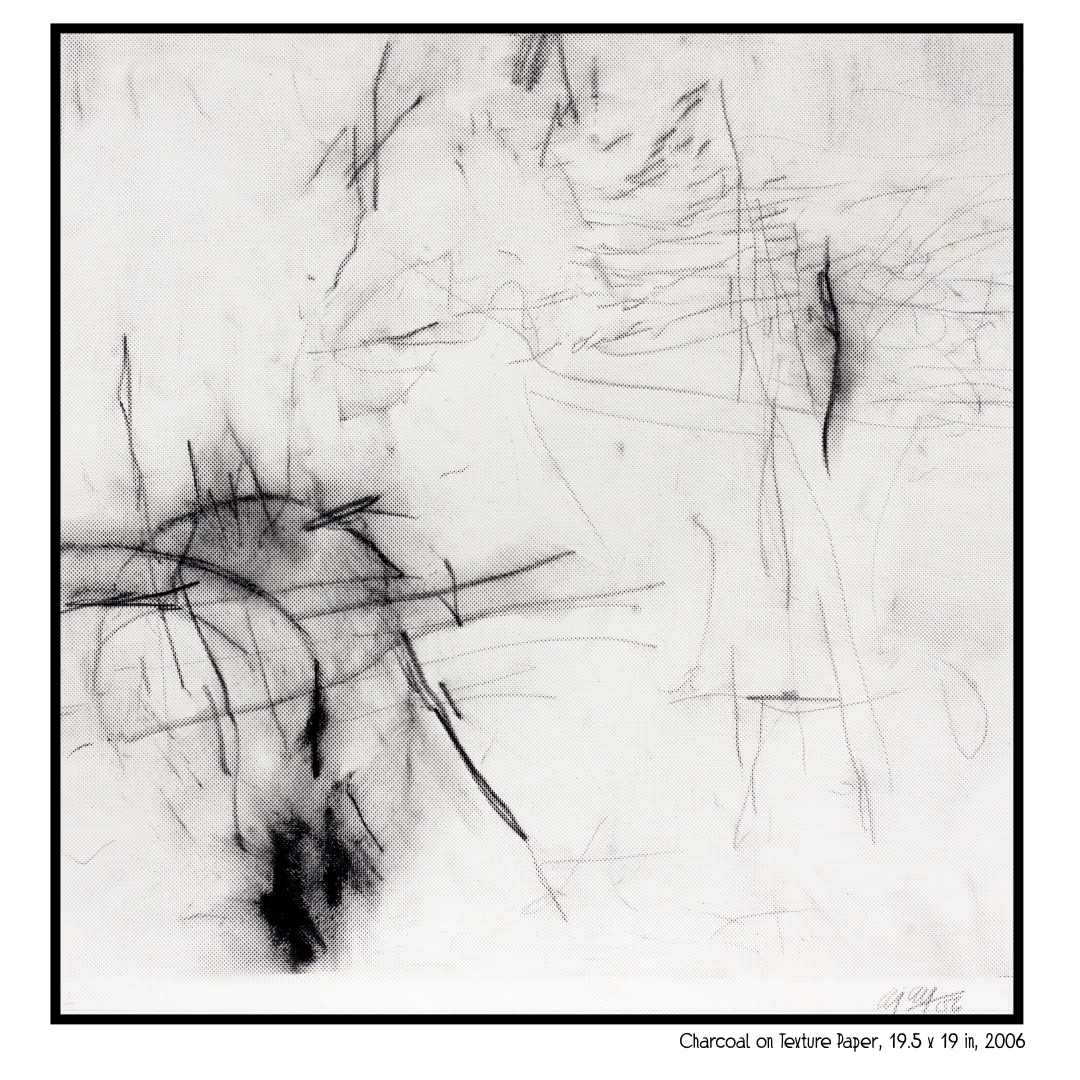

Artwork by Ajay Choudhary.

What is most readily apparent in Ajay Choudhary’s work both his paintings and his drawings is the openness with which he approaches each canvas or sheet of paper. If there is a plan or a blueprint in mind, then it is truly only there, in the mind, for the images themselves be speak nothing less than a complete visual autonomy period of studio concentration where “now” is the directive and “let it happen” the mantra. Sculptor Donald Judd once ventured that the artist’s fiercest adversary was “composition,” and in turn the “juggling. jockeying, fussing. [and] balancing” needed to get there. (1) This is not to say that the idea of composition is to be avoided at all costs, certainly Judd’s perfectionist objects involved a great deal of planning and forethought, but there are unquestionable creative benefits that come with spontaneity, and certainly, Choudhary is no stranger to their attraction.

STRUCTURE & BISECTION

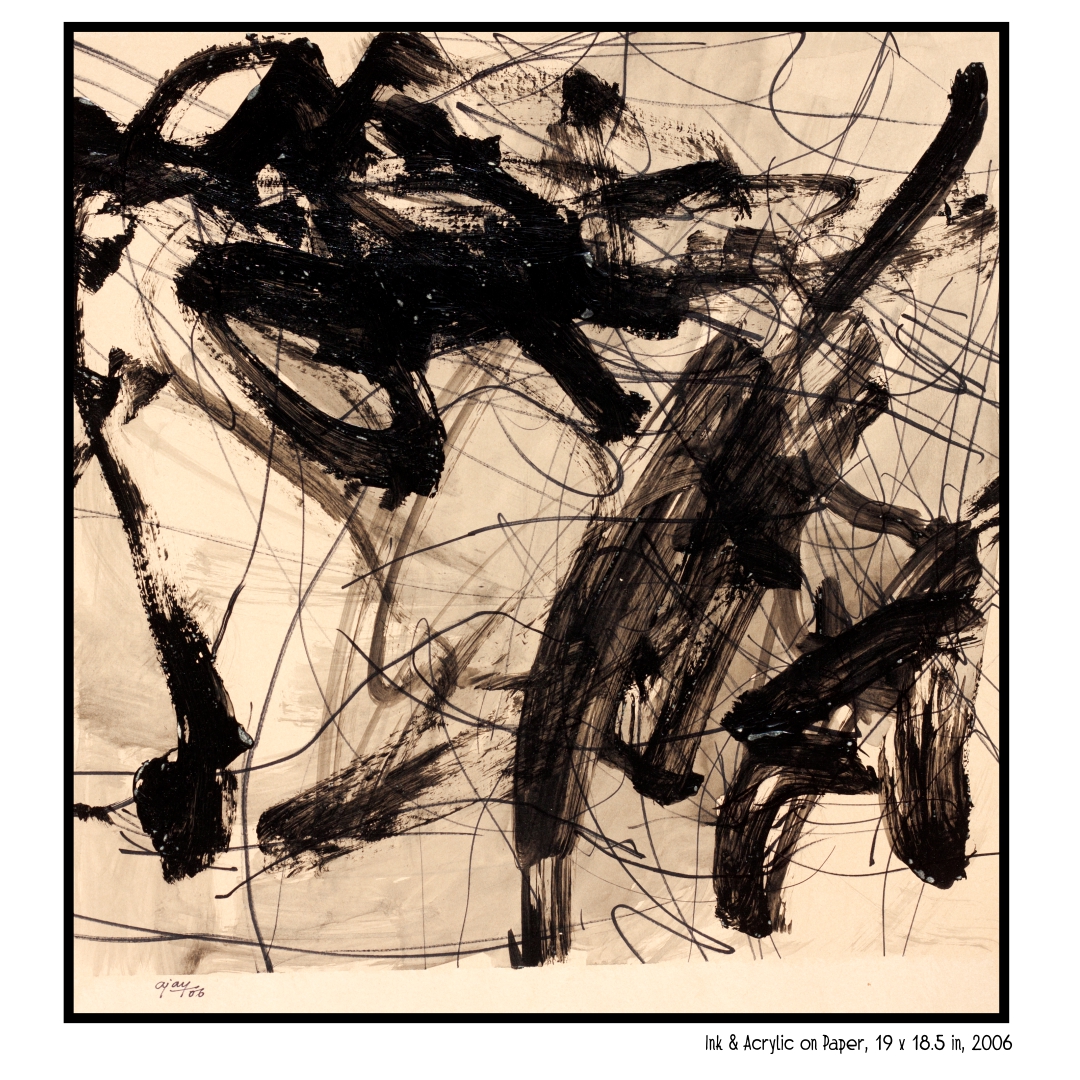

Painting by Ajay Choudhary.

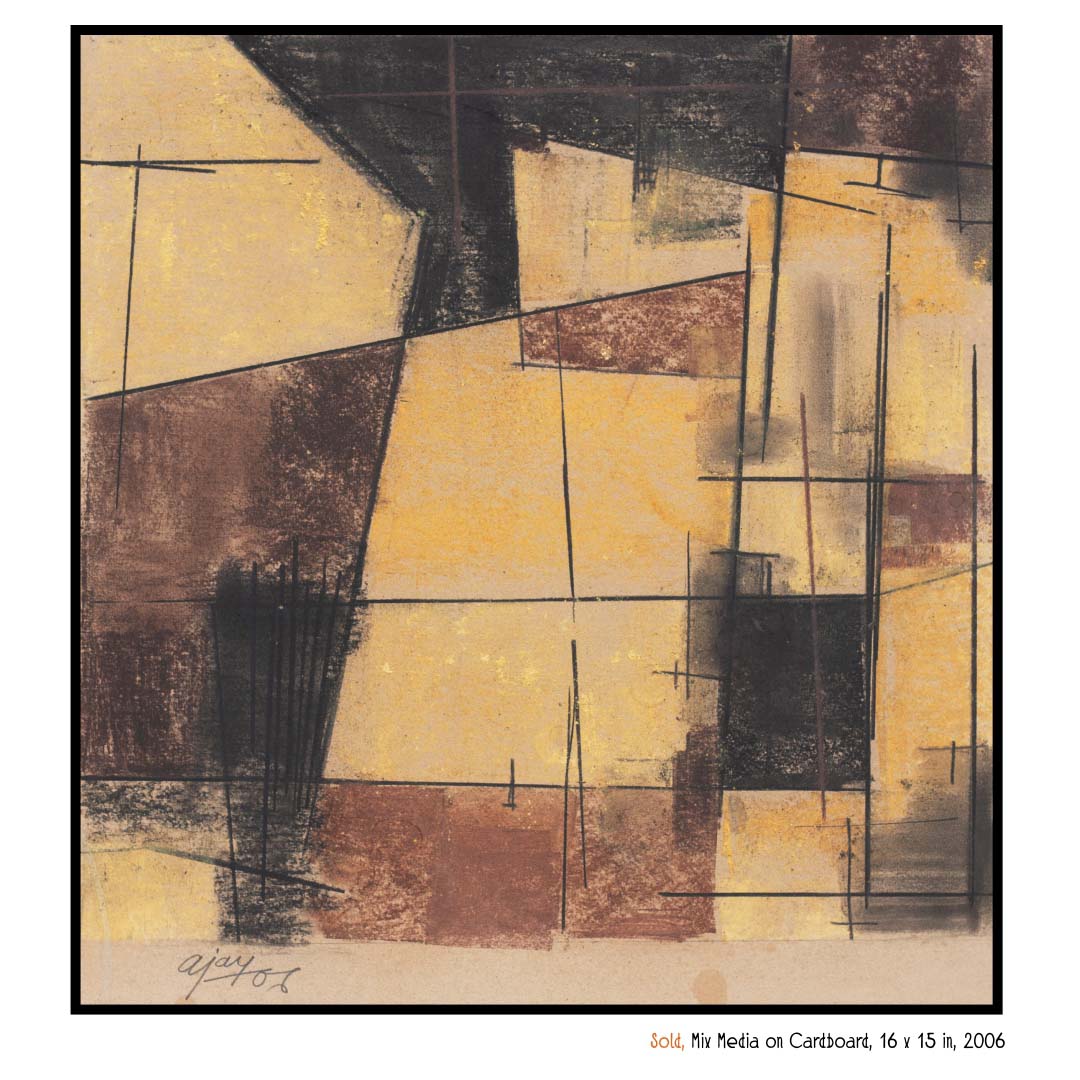

Frank Stella, like just about all of his immediate successors, was admittedly interested in “explor[ing] the integral relationship between surface and support.” (2) The working area, be it canvas, panel, or paper, is a field, and must be addressed as such regardless of what is rendered atop it. “When [Richard] Diebenkorn wants to set a curve flowing across the paper,” wrote critic Robert Hughes in Time magazine in 1982, “Its rhythm acquires a detached mellowness, a quality or reverie,” yet “this wandering of the hand is constantly checked and inflected by the vestiges of a grid.” (3) Inescapable as it is, there are varied means of approaching the actuality of the geometry of the working area. Instead of defining the crisscross pattern, the structural element with which the paper and the canvas can be bisected, Choudhary’s modus operandi is to unravel and untwist it into a maze of free lines.

Each “compartment” the lines make upon intersecting is filled alternately with the fleshy background color or its slathered sienna and tan compliment. In places, the lines act as boundaries, containing the paint forms. In others they ignore their surroundings completely, meandering through the different terrains unaware, or at least unobservant of their surroundings. In some of the drawings, we see traces of past lines through foundation background hues. Forgotten in places, half-excavated in others, these hints of some type of underlying mesh tell of history in the work, a past that the artist wants us to be aware of but not too familiar with.

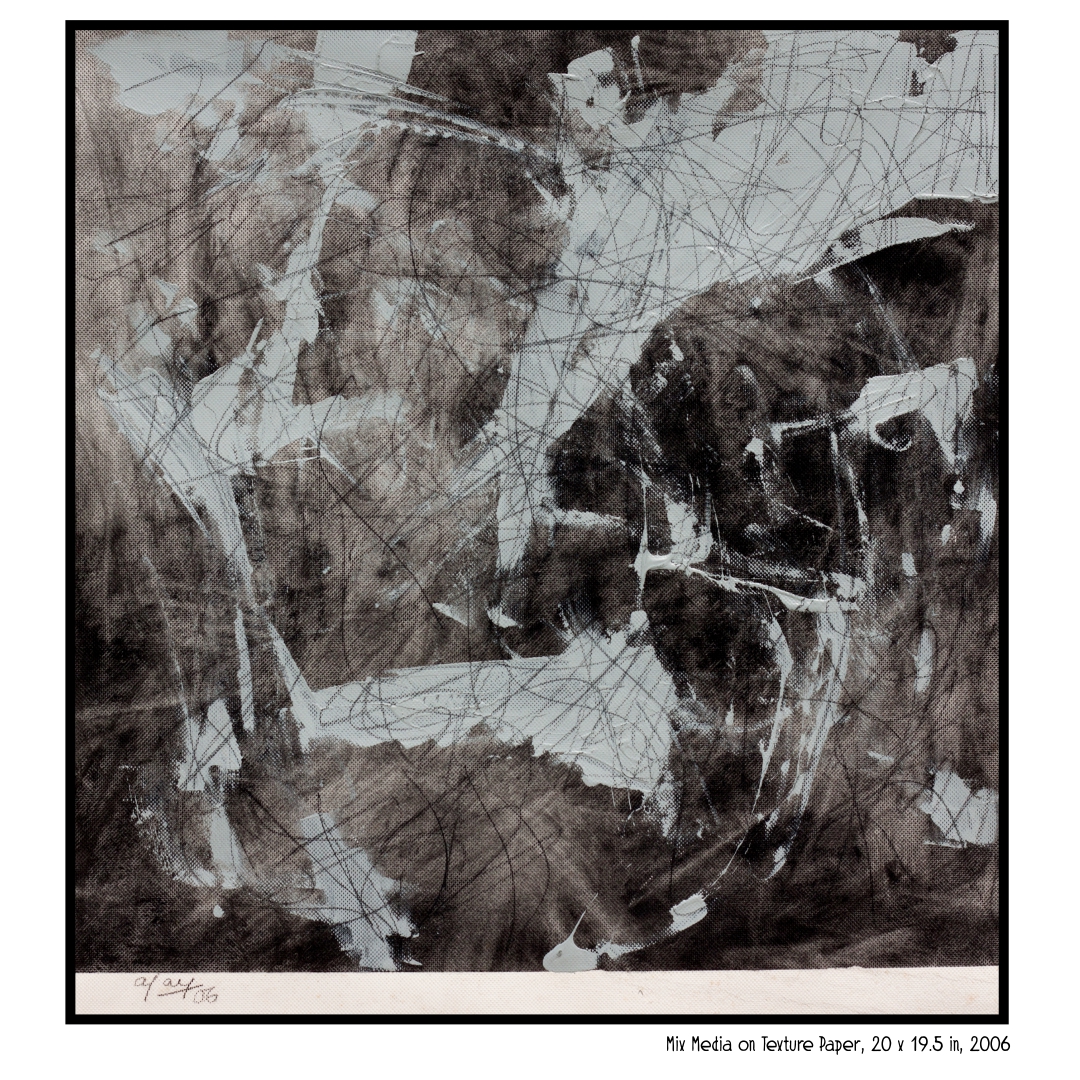

SQUIBBLY

While Diebenkorn transported his seaside Los Angles vistas into blocks of blue and humps of sandy warmness. Choudhary’s periphery encompasses the brown expanses of Gujarat checkered with the olives and fatigue cultivation and vegetation. In the sky birds circle and figure-eight above. While the artist’s hand mimics their trajectories in squiggly lines. Just as “images of the California coast have found their way” into Diebenkorn’s works, the panoramas and palettes of the Indian mise en scène have infiltrated these drawings; but, as Hughes pointed out, “in a condensed and fully digested idiom whose sources, far back in the early twentieth century, are Henri Matisse and Piet Mondrian.”

PRIMITIVE ART

Yet aside from the thematic. Choudhary seemingly shuns subject matter altogether, at least superficially. The medium is his subject, constantly being molded and formed into what it will become, an abstraction. “The medieval artist, like the child, relies on the minimum schema needed to ‘make’ a house, a tree, a boat that can function in the narrative,” writes E.H. Gombrich in his psychological study Art and Illusion. “When we say these schemata look somewhat like toy trees or toy boats, we are presumably closer to the explanation of the essentials of ‘primitive art’,” or the origin of visual representation. On the other hand, someone like John Constable, for instance, throws a wrench in the whole process by making “allowance for the transformations which shapes and colors undergo through the accident of the position from which he viewed the scene. Taking their real shape for granted, he modifies them even at the risk of sacrificing functional clarity.” (5)

CUBIST EXPRESSIONISTS

Continue this line of reasoning, of perpetual modification, and you wind up with the abstractions of the Cubists, the Abstract Expressionists, and presently of Choudhary. Observation need not be based on mimicry, lest the sublime be glossed over. Painter Richard Lytle, one of MOMA’s 16 Americans, directs our attention to an entry in Delacroix’s diary that declared most people see objects only literally. “Of the exquisite, they see nothing.” (6)

DEPARTURE & CONTINUATION

Like Diebenkorn’s 1982 exhibition of which Hughes spoke, Choudhary’s decision to exclude the formality of painting in favor of these relatively hurried selections, ” marks both a departure and a continuation.” As opposed to his rich-hued oil paintings. Choudhary’s drawings exist as more than just “sketches” for explorations to be made later backed up with paint-laden brushes. They are furtive excursions (or more appropriately incursions) into a territory not necessarily extant in the three dimensions we move freely about in our daily lives. It is a skeletal world, gridded up and framed, where puce moments share space with the winding ink line that chases the artist’s pen around the paper. These drawings give the impression of a web hanging in space Brown and tan vapors float and spin suspended. Bled to the edges of the paper, the space is abruptly chopped, leading the viewer to imagine massive vistas beyond. Of what we’re unsure. Perhaps more of the same, or perhaps these drawings have captured just the beginning, the edge or outlying areas of something vaster, more massive, and more solid, with colors, opacity, and mass. Like an oil painting.

Written by

Erik Bluhm

Critique-Art America

Los Angeles, USA.

Notes:

- Cooper, Harry, “What You See and What He Said.” Frank Stella 1958. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006. (73)

- Luke, Megan R. “Objecting to Things.” Frank Stella 1958. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006. (41)

- Hughes, Robert. “Richard Diebenkorn.” Nothing if Not Critical Selected Essays on Art and Artists. New York: Penguin Books 1992. (279)

- Ibid.

- Gombrich, E.H. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1960. (295)

- Miller, Dorothy C. (ed.). Sixteen Americans. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959. (42)

Photos and Text © Chaitya Dhanvi Shah

printing, distribution or copying of this text/images without permission is not allowed.